- Home

- PHOTO GALLERY

- Sluice Hill

- Reeds Station

- Rangeley

- Langtown

- Eustis Junction

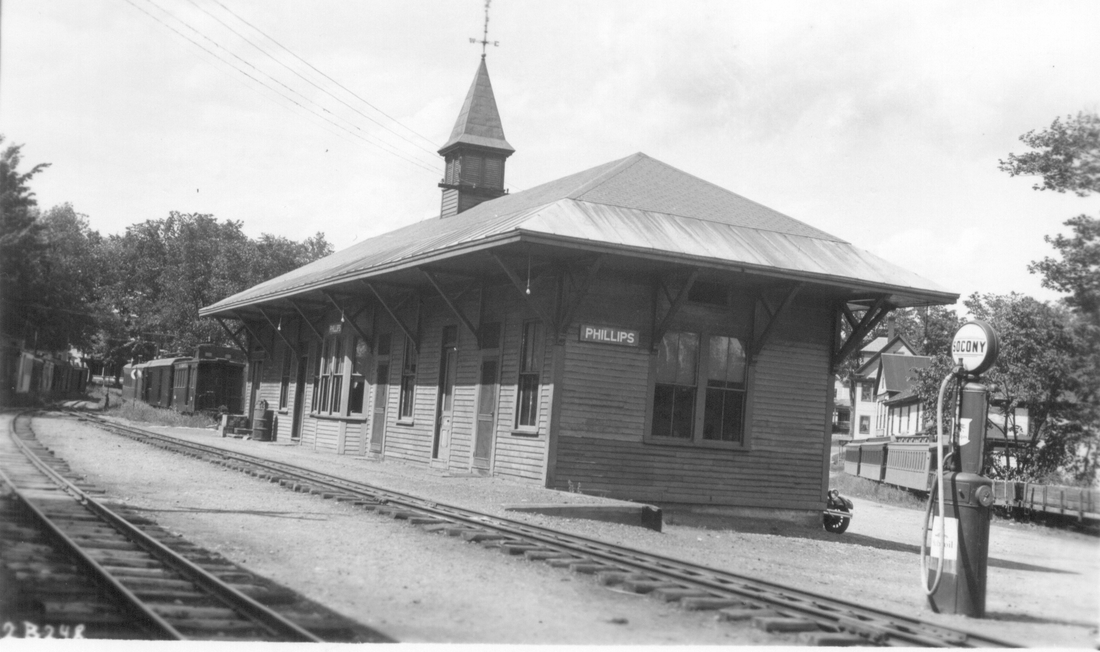

- Phillips

- Salmon Hole

- Avon

- Porter Brook

- Strong

- Farmington

- PLANNING THE LAYOUT

- Locomotives and Motive Power

- Rolling Stock

- F & C KIT BUILDING TUTORIAL

- PASSENGER CARS

- CABEESE

- SR&RL Structure Kits

- Other Maine 2-Foot Structure Kits

- Operations

- Behind the Scenes

- Logs and Stumps

- SR&RL LIBRARY

- Franklin and Bath Railroad

- Big Boats and Small Ships

- HOn30 Maine Two Foot Modeling Links

- RAIL FEST 2019

- VEHICLES

- About Me

- MODELING IN HOn30

- MY MODELING PHILOSOPHY

- Links

MY MODELING PHILOSOPHY

Well first and foremost, as I mentioned on another page, I didn't take the hobby back up from my childhood until 2017 at the age of 55, and I did it to spend my time doing something enjoyable and rewarding. Well, it certainly has filled those desires.

There are many, many compromises that you have to make when building a layout. Knowing I would have to make compromises, I set a mental standard for myself. Ideally, in a perfect world, I would have an exact model of Franklin County Maine during the age of the Sandy River & Rangeley Lakes Railroad, sometime between 1900 and 1930, with a realistically operating model of that railroad in HOn30 scale. But that's not possible, so I had to set the standard for my compromises. My decisions in the back of my mind would be that the trains would have to be as realistic as possible, the track plan would have to follow the original as closely as possible, the terrain and scenery would have to look as close to that actually in Franklin County as possible, and there would have to be enough readily recognizable buildings and features so that when one viewed any particularly important part of the layout, they could immediately recognize it for the actual area modeled. In example, getting comments like "wow, that really looks like the Phillips roundhouse and yard", or "hey! the covered railroad bridge!" or "wow, you actually modeled the Rangeley lake House". Those are the comments I would shoot for in my modeling.

Ideally, the railroad will operate on Timetable and Train Orders, the layout structures will be lit so that it can be operated in the dark hours, ultimately, the trains will be converted to DCC with sound, a fast clock will be employed set to automatic room lighting that brightens and darkens with the time of day on the fast clock, and sound effects will be added with sensors so that when you operate around a sawmill, sawmill sounds automatically kick in. Those are the goals.

This is a big project, as is any layout, even a small one. So there are a million questions to be answered and a million problems to be solved, and a million things to learn and a million little pieces to be put together.

With all that information, the first thing that comes to my mind about how I can employ that information, is the word pragmatic: dealing with things sensibly and realistically in a way that is based on practical rather than theoretical considerations. Everything is a problem to be solved, and how am I going to go about solving it within the limitations I have and the ways I have available. My limitations are time, money, space available, and skills.

TIME

Well, I'm totally retired so time to work on the railroad isn't much of a consideration. However, I want to get this layout done before I'm dead, or at least before I'm too old to enjoy the finished product. So there are time limitations on how much I can spend on any one sub-task. For instance, if I wanted every tree on the layout to be a near-perfect tree, all I would have done on the layout before I'm dead is a whole lot of model trees. So I don't do things like detailed building interiors unless it's a store front that will be lit at night with large windows, I have overcome my aversion to not adding complete walls with windows and whatnot to the backs of buildings that can't be seen, etc. After a couple of years of experimenting around with different methods of doing different things, I have pretty much settled into standard techniques that suit me for doing most things that need to be done. This speeds up work a lot, because things get done by habit, not pondering 'how am I going to do this' for hours/days/weeks/months.

I'm told I work very fast, which I suppose by this point I kind of do because of these standard processes I use for everything, but that is also a trade-off. No one thing that I do is going to win any awards, but when all these sub-elements are combined together in a scene, no-one notices that any one element isn't award-worthy. It's the 'not seeing the forest for the trees' thing or however the saying goes. I could spend a week building a great sawmill building, or I could spend a week building a good-looking sawmill complete with yard and workers and vehicles emplaced in a picturesque couple of square feet of terrain. I go for the latter, because completing the layout in a timely manner is a primary goal.

There are many, many compromises that you have to make when building a layout. Knowing I would have to make compromises, I set a mental standard for myself. Ideally, in a perfect world, I would have an exact model of Franklin County Maine during the age of the Sandy River & Rangeley Lakes Railroad, sometime between 1900 and 1930, with a realistically operating model of that railroad in HOn30 scale. But that's not possible, so I had to set the standard for my compromises. My decisions in the back of my mind would be that the trains would have to be as realistic as possible, the track plan would have to follow the original as closely as possible, the terrain and scenery would have to look as close to that actually in Franklin County as possible, and there would have to be enough readily recognizable buildings and features so that when one viewed any particularly important part of the layout, they could immediately recognize it for the actual area modeled. In example, getting comments like "wow, that really looks like the Phillips roundhouse and yard", or "hey! the covered railroad bridge!" or "wow, you actually modeled the Rangeley lake House". Those are the comments I would shoot for in my modeling.

Ideally, the railroad will operate on Timetable and Train Orders, the layout structures will be lit so that it can be operated in the dark hours, ultimately, the trains will be converted to DCC with sound, a fast clock will be employed set to automatic room lighting that brightens and darkens with the time of day on the fast clock, and sound effects will be added with sensors so that when you operate around a sawmill, sawmill sounds automatically kick in. Those are the goals.

This is a big project, as is any layout, even a small one. So there are a million questions to be answered and a million problems to be solved, and a million things to learn and a million little pieces to be put together.

With all that information, the first thing that comes to my mind about how I can employ that information, is the word pragmatic: dealing with things sensibly and realistically in a way that is based on practical rather than theoretical considerations. Everything is a problem to be solved, and how am I going to go about solving it within the limitations I have and the ways I have available. My limitations are time, money, space available, and skills.

TIME

Well, I'm totally retired so time to work on the railroad isn't much of a consideration. However, I want to get this layout done before I'm dead, or at least before I'm too old to enjoy the finished product. So there are time limitations on how much I can spend on any one sub-task. For instance, if I wanted every tree on the layout to be a near-perfect tree, all I would have done on the layout before I'm dead is a whole lot of model trees. So I don't do things like detailed building interiors unless it's a store front that will be lit at night with large windows, I have overcome my aversion to not adding complete walls with windows and whatnot to the backs of buildings that can't be seen, etc. After a couple of years of experimenting around with different methods of doing different things, I have pretty much settled into standard techniques that suit me for doing most things that need to be done. This speeds up work a lot, because things get done by habit, not pondering 'how am I going to do this' for hours/days/weeks/months.

I'm told I work very fast, which I suppose by this point I kind of do because of these standard processes I use for everything, but that is also a trade-off. No one thing that I do is going to win any awards, but when all these sub-elements are combined together in a scene, no-one notices that any one element isn't award-worthy. It's the 'not seeing the forest for the trees' thing or however the saying goes. I could spend a week building a great sawmill building, or I could spend a week building a good-looking sawmill complete with yard and workers and vehicles emplaced in a picturesque couple of square feet of terrain. I go for the latter, because completing the layout in a timely manner is a primary goal.

MONEY

Money is of course a project killer for any hobby other than going for a walk or breathing. I am fortunate in that I'm retired with a pension and benefits, and I ran a business on the side for 20 years and made several wise investments over my adulthood. Over the years I also built a large collection of military antiques, so I can also sell off pieces that I don't care about anymore for additional funding for my railroad.

One thing about money though- a penny saved really is a penny earned. If I can save money in one area, that means I have more money to spend in another area. I buy a lot of used stuff, half-built kits, use coupons, make offers on ebay whenever it's an option, and one of my favorite pastimes at model railroad shows is digging through the bins of 'junk' that vendors have below their tables looking for deals. You find a lot of things such as for example, a Jordan Highway Miniatures Steam Shovel model for $7 talked down to $6 that goes for over $50 on Ebay. Or a steamboat kit for $10 that goes for $49 retail, or several bags of barely used ground foam for $5 that would retail for $40 or more. I once bought a craftsman waterfront diorama kit for $60 that I turned around and sold on Ebay for $240, quadrupling my money that I could put into an expensive brass loco.

Another thing is scratch-building. Sometimes if a structure is available commercially, like the Strong Depot, I'll buy it because I don't have to figure anything out (the manufacturer got paid to do that) and kits build quickly. But if you compare the Strong Depot kit that costs somewhere around $90, and the similarly designed Reeds depot that I scratch built, the Reeds depot cost a couple of dollars worth of stock plastic from a bin under a table, a couple of dollars worth of Grandt Line window and door castings, some scrap cardboard, and a few cents worth of Campbell shingles from a bind under a table. I doubt it cost more than $9 to build, so 1/10 of the Strong Depot kit. I box of 4 or 5 commercially built trees from the usual manufacturers might cost $12 or more, whereas buying a $29 dollar box of Super Trees can yield 80 trees or more by adding a bag of poly fiber and a bag of green ground foam, both preferably bought from a bin under someone's table.

One of my most useful buys ever, if you can call it that, was a large box of partically used acrylic craft paints. I say if you can call it a buy, because I had amassed a large pile of stuff from the bins of one of my favorite train show vendors, and when he tallied everything up, he asked me if I could use this big box of partially used paints sitting on the table. I said I'm sure I could and asked him how much, and he pushed the box up to my pile and said "nothing". That began my conversion to what one of my friends calls "crappy craft store acrylics", which are a fraction of the cost of modeling paints and come in an amazing variety of colors.

Another thing that I do with almost every purchase is comparison shop. If I discover something that I want, from whatever source, I immediately do research. I'll see what I can get it for on Amazon, see what I can get it for from other dealers, and see what I can get it for on ebay. I'll go for the cheapest price, and if it's a little more expensive on Amazon than the other sources, I might wait for the end of the month when I get my rewards points for my Amazon card and use points instead of money out of my pocket. Or I might put the thing on my watch list on Ebay and do searches under "Newly Listed" over time to see if I can get a better deal. I always use coupons at Hobby Lobby and JoAnne Fabrics (yes, you can find model railroad supplies there, like big bags of lychen cheap in useful colors).

So the bottom line I guess on money, is that there are plenty of ways to maximize the money that you have. If I had to quantify the expense of my layout, I would estimate that if I paid full retail price for everything I've completed, it would have cost me at least twice what I've actually spent, and I wouldn't doubt that if it could be tabulated, it might be three times what I actually spent.

Money is of course a project killer for any hobby other than going for a walk or breathing. I am fortunate in that I'm retired with a pension and benefits, and I ran a business on the side for 20 years and made several wise investments over my adulthood. Over the years I also built a large collection of military antiques, so I can also sell off pieces that I don't care about anymore for additional funding for my railroad.

One thing about money though- a penny saved really is a penny earned. If I can save money in one area, that means I have more money to spend in another area. I buy a lot of used stuff, half-built kits, use coupons, make offers on ebay whenever it's an option, and one of my favorite pastimes at model railroad shows is digging through the bins of 'junk' that vendors have below their tables looking for deals. You find a lot of things such as for example, a Jordan Highway Miniatures Steam Shovel model for $7 talked down to $6 that goes for over $50 on Ebay. Or a steamboat kit for $10 that goes for $49 retail, or several bags of barely used ground foam for $5 that would retail for $40 or more. I once bought a craftsman waterfront diorama kit for $60 that I turned around and sold on Ebay for $240, quadrupling my money that I could put into an expensive brass loco.

Another thing is scratch-building. Sometimes if a structure is available commercially, like the Strong Depot, I'll buy it because I don't have to figure anything out (the manufacturer got paid to do that) and kits build quickly. But if you compare the Strong Depot kit that costs somewhere around $90, and the similarly designed Reeds depot that I scratch built, the Reeds depot cost a couple of dollars worth of stock plastic from a bin under a table, a couple of dollars worth of Grandt Line window and door castings, some scrap cardboard, and a few cents worth of Campbell shingles from a bind under a table. I doubt it cost more than $9 to build, so 1/10 of the Strong Depot kit. I box of 4 or 5 commercially built trees from the usual manufacturers might cost $12 or more, whereas buying a $29 dollar box of Super Trees can yield 80 trees or more by adding a bag of poly fiber and a bag of green ground foam, both preferably bought from a bin under someone's table.

One of my most useful buys ever, if you can call it that, was a large box of partically used acrylic craft paints. I say if you can call it a buy, because I had amassed a large pile of stuff from the bins of one of my favorite train show vendors, and when he tallied everything up, he asked me if I could use this big box of partially used paints sitting on the table. I said I'm sure I could and asked him how much, and he pushed the box up to my pile and said "nothing". That began my conversion to what one of my friends calls "crappy craft store acrylics", which are a fraction of the cost of modeling paints and come in an amazing variety of colors.

Another thing that I do with almost every purchase is comparison shop. If I discover something that I want, from whatever source, I immediately do research. I'll see what I can get it for on Amazon, see what I can get it for from other dealers, and see what I can get it for on ebay. I'll go for the cheapest price, and if it's a little more expensive on Amazon than the other sources, I might wait for the end of the month when I get my rewards points for my Amazon card and use points instead of money out of my pocket. Or I might put the thing on my watch list on Ebay and do searches under "Newly Listed" over time to see if I can get a better deal. I always use coupons at Hobby Lobby and JoAnne Fabrics (yes, you can find model railroad supplies there, like big bags of lychen cheap in useful colors).

So the bottom line I guess on money, is that there are plenty of ways to maximize the money that you have. If I had to quantify the expense of my layout, I would estimate that if I paid full retail price for everything I've completed, it would have cost me at least twice what I've actually spent, and I wouldn't doubt that if it could be tabulated, it might be three times what I actually spent.

SPACE AVAILABLE

MY model railroad room is 12'5" x 18'3". I achieved that by ripping out the closets and cabinet at one end of the room. I originally hoped to model Barnjum, Madrid and Redington in addition to what I'm able to cram in, but realized as I progressed I simply couldn't fit them in. So I compromised. I decided what I simply HAD to have, which was Rangeley, Phillips, Strong and Farmington, and then figure out what I could model that was in between each of those points.

Of all the compromises you have to make in model railroading, I think space available is the biggest. If I modeled the Farmington yard in actual 1/87 scale, it would take up the entire space I have in the room, if not more. So pretty much everything has to be compressed. My yards aren't scale size, the distances in between aren't and many of the buildings aren't.

My entire layout could be considered to be selectively compressed; compressed yards, compressed buildings, compressed towns, compression all over the place. It helps get more of what I want into the finite space available.

Another thing about space, is the wider the layout is from walls and into aisle space, the less scale track mileage you're gonna get on your layout. The widest spots on my layout from walls or free-standing backdrops are 30". Those are spots where towns and yards are located. To make areas on the layout look wider/deeper than they are, I use photo backdrops and forced perspective. Another thing I do in several places is move the track back into the scenery, not along the front edge, and employ lots of curves and scenery blocks. Following the train through the landscape from scene to scene makes the trip seem longer than it really is. Keeping your benchwork narrow allows you to route your railroad through more of the room. A giant mountain that reaches up to the ceiling and takes up a space 6' wide and 8' long with the train running around the base of it may look really cool, but that space could be much better used putting in industries to service and using a photo backdrop for the mountain scene instead, and allowing a 2' wide shelf with a yard, with a 20" radius at one end going around a 30' aisle with more track on an 18" peninsula in that same 6'x8' space.

MY model railroad room is 12'5" x 18'3". I achieved that by ripping out the closets and cabinet at one end of the room. I originally hoped to model Barnjum, Madrid and Redington in addition to what I'm able to cram in, but realized as I progressed I simply couldn't fit them in. So I compromised. I decided what I simply HAD to have, which was Rangeley, Phillips, Strong and Farmington, and then figure out what I could model that was in between each of those points.

Of all the compromises you have to make in model railroading, I think space available is the biggest. If I modeled the Farmington yard in actual 1/87 scale, it would take up the entire space I have in the room, if not more. So pretty much everything has to be compressed. My yards aren't scale size, the distances in between aren't and many of the buildings aren't.

My entire layout could be considered to be selectively compressed; compressed yards, compressed buildings, compressed towns, compression all over the place. It helps get more of what I want into the finite space available.

Another thing about space, is the wider the layout is from walls and into aisle space, the less scale track mileage you're gonna get on your layout. The widest spots on my layout from walls or free-standing backdrops are 30". Those are spots where towns and yards are located. To make areas on the layout look wider/deeper than they are, I use photo backdrops and forced perspective. Another thing I do in several places is move the track back into the scenery, not along the front edge, and employ lots of curves and scenery blocks. Following the train through the landscape from scene to scene makes the trip seem longer than it really is. Keeping your benchwork narrow allows you to route your railroad through more of the room. A giant mountain that reaches up to the ceiling and takes up a space 6' wide and 8' long with the train running around the base of it may look really cool, but that space could be much better used putting in industries to service and using a photo backdrop for the mountain scene instead, and allowing a 2' wide shelf with a yard, with a 20" radius at one end going around a 30' aisle with more track on an 18" peninsula in that same 6'x8' space.

SKILLS

My first layout when I was a kid was the usual HO oval on a 4'x8' sheet of plywood. I added three manual turnouts at some point for a siding and a spur. The only thing electronic was the throttle pack. The buildings were whatever I had money for from the local hobby shop, built straight from the box with no paint, and the scenery was green sawdust on house paint. I had a few Bachmann trees, and the people were factory painted (poorly) with little round bases. Improvements in looks were something I read about in Model Railroader and Railroad Model Craftsman, but imagined someday I'd be able to do myself. My big purchases were a 2-8-0 Consolidation and a 4-6-2 Pacific, both of which I ordered from the ads in the magazines, and paid for C.O.D. (cash on delivery) when the delivery man showed up with them at our house.

I got a big culture shock in 2017. The internet had changed everything about model railroading, and technology was light years ahead of what I remembered. I had to make more decisions on how I was going to go about this. After briefly joining a local model railroad club and learning some basics about DCC, I decided I'd stick, at least at first, to DC and build it with blocks the way the pro's did it in the old days, which is what I imagined myself doing someday. As of this writing, I still do everything pretty much manually. I have a couple of air brushes that I have yet to use, all my painting and weathering is by hand. I do use spray cans for things like priming or painting batches of tree armatures and whatnot. I don't have a 3-D printer, laser cutter, or pretty much anything sophisticated other than a mini-chop saw and a Dremel tool.

Everything you see in my work is something I learned from someone else. I have often said that I don't have an original bone in my body, but I can copy just about anything. I've acquired almost all of my techniques by reading Kalmbach books, and the rest from either other modelers' books or occasionally YouTube videos. I read what others say about how to do a particular technique and look at photos, then try it out, and amazingly, most of the time mine looks like the expert's does. Some things don't work out, other things work better than I imagined, and after doing these things for a while, it becomes second nature. The biggest thing I can say about becoming skilled, is you eat an elephant one bite at a time, and the more bites you take, the better you get at eating that critter. The same thing with modeling. None of this stuff is complicated, and there's no magic or mystery to good modeling, just learning simple techniques from others who've gotten good at it themselves.

My first layout when I was a kid was the usual HO oval on a 4'x8' sheet of plywood. I added three manual turnouts at some point for a siding and a spur. The only thing electronic was the throttle pack. The buildings were whatever I had money for from the local hobby shop, built straight from the box with no paint, and the scenery was green sawdust on house paint. I had a few Bachmann trees, and the people were factory painted (poorly) with little round bases. Improvements in looks were something I read about in Model Railroader and Railroad Model Craftsman, but imagined someday I'd be able to do myself. My big purchases were a 2-8-0 Consolidation and a 4-6-2 Pacific, both of which I ordered from the ads in the magazines, and paid for C.O.D. (cash on delivery) when the delivery man showed up with them at our house.

I got a big culture shock in 2017. The internet had changed everything about model railroading, and technology was light years ahead of what I remembered. I had to make more decisions on how I was going to go about this. After briefly joining a local model railroad club and learning some basics about DCC, I decided I'd stick, at least at first, to DC and build it with blocks the way the pro's did it in the old days, which is what I imagined myself doing someday. As of this writing, I still do everything pretty much manually. I have a couple of air brushes that I have yet to use, all my painting and weathering is by hand. I do use spray cans for things like priming or painting batches of tree armatures and whatnot. I don't have a 3-D printer, laser cutter, or pretty much anything sophisticated other than a mini-chop saw and a Dremel tool.

Everything you see in my work is something I learned from someone else. I have often said that I don't have an original bone in my body, but I can copy just about anything. I've acquired almost all of my techniques by reading Kalmbach books, and the rest from either other modelers' books or occasionally YouTube videos. I read what others say about how to do a particular technique and look at photos, then try it out, and amazingly, most of the time mine looks like the expert's does. Some things don't work out, other things work better than I imagined, and after doing these things for a while, it becomes second nature. The biggest thing I can say about becoming skilled, is you eat an elephant one bite at a time, and the more bites you take, the better you get at eating that critter. The same thing with modeling. None of this stuff is complicated, and there's no magic or mystery to good modeling, just learning simple techniques from others who've gotten good at it themselves.

A FEW PARTICULARS ABOUT MY LAYOUT

Perfect?

Somewhere back in my past, I heard or read someone make the statement, "The perfect is the enemy of the good". I took that to heart, and it has served me well in both my work life and leisure life. I touched on it with the sawmill analogy above. I like using the naval pilot programs of the United States and Japan in WW2 as an example. The Japanese spent years training and developing their naval pilots to become arguably the best in the world at the beginning of the war, and swept the skies of Asia and the Pacific of everything that didn't have a red ball painted on it in the first 6 months of the war. The pilots they fought against didn't have experience and often were using inferior equipment. The Japanese pilots were "perfect". But the United States and its allies embarked on a program of training thousands of "good" pilots and flooding the skies with them. By the end of 6 months, the Japanese were losing their edge as they inevitably lost "perfect" pilots that they couldn't replace, and by the end of the first year of the war, the writing was already on the wall for the Japanese. The object of training pilots for war is winning the war, not having the best pilots.

The object of my layout building is to build a layout, not achieve perfect model building.

I decided early while getting back into the hobby that I was going to just do this for enjoyment, and that I would just make it all "good enough" to make myself happy. I can guarantee you that if you look closely at my work, you'll find flaws all over the place. I hate rain gutters and drainpipes, so you won't find a single one in my work. My scratch-built buildings may readily be identifiable for what they are, such as the International Mill at Phillips. But comparing it side by side with photos of the original, it's not even close to being a scale model of the original. I use measurements to fit the space available for things, balance it with measurements of window frames and whatnot, and then build it to LOOK like the original, not be a SCALE MODEL of the original. I'm sure a lot of modelers frown on this kind of an approach, but when it comes down to it, only a handful of people in the world might be familiar enough with the International Mill to even know what it is, to say nothing about critiquing the model.

Whether it's scenery building, making rolling stock, painting and weathering locos, or whatever, if you're shooting for perfection instead of good, you're never going to be able to actually build a finished layout and working railroad, unless you spend decades working on it. But even then, probably not.

The object of my layout building is to build a layout, not achieve perfect model building.

I decided early while getting back into the hobby that I was going to just do this for enjoyment, and that I would just make it all "good enough" to make myself happy. I can guarantee you that if you look closely at my work, you'll find flaws all over the place. I hate rain gutters and drainpipes, so you won't find a single one in my work. My scratch-built buildings may readily be identifiable for what they are, such as the International Mill at Phillips. But comparing it side by side with photos of the original, it's not even close to being a scale model of the original. I use measurements to fit the space available for things, balance it with measurements of window frames and whatnot, and then build it to LOOK like the original, not be a SCALE MODEL of the original. I'm sure a lot of modelers frown on this kind of an approach, but when it comes down to it, only a handful of people in the world might be familiar enough with the International Mill to even know what it is, to say nothing about critiquing the model.

Whether it's scenery building, making rolling stock, painting and weathering locos, or whatever, if you're shooting for perfection instead of good, you're never going to be able to actually build a finished layout and working railroad, unless you spend decades working on it. But even then, probably not.

What, when and where?

What year do I model? What season do I model? What do I emphasize as the purpose of the railroad? These are the questions one is often asked or asks of oneself for the layout.

Well I wanted to have as much of my cake as I could and eat it too, so I cleverly devised a plan. Different areas of the layout represent different decades and different seasons. That way I can use horses, Model T's and Model A's as well as model specific industries and whatnot that appeared and disappeared in Franklin County at the bat of an eye. The history of this railroad is such that rarely a year passes when new spurs and sidings appeared and disappeared, mills were opened or closed or literally picked up and moved to new locations. New locomotives came, old went, and some old were rebuilt into new configurations. Towns were born, grew, and disappeared. Researching all of this quickly makes you realize that you simply can't nail down what the railroad and the county looked like at any given point in any given year. Which makes it easier to justify decisions you make in what you're modeling.

Modeling all four seasons allows me to try my hand at portraying summer, fall, winter and spring, and while I'm at it, I decided I'd see how convincing a job I could do of transitioning from season to season as you move along the layout, not simply bluntly going from one season to the next.

My personal favorite aspect of the railroad was the era when Rangeley was a famous and busy resort town, full of hotels and camping lodges, steamboats and hunting guides, golf courses, sawmills, movie houses playing the latest Charlie Chaplin films and all of it serviced by the blood stream of the two-footer. To make Rangeley really come alive, it needed to be modeled in the summer, so I decided that the layout would be anchored at Rangeley in the summer, then transition to Phillips in the fall, then transition to Strong in the winter, and end at the other end of the line in the spring.

I wanted Rangeley's decade to be 1900-1910, during the heyday of the resorts, with stage coaches still operating, horse drawn wagons and very early autos owned by the rich being the norm. Phillips is 1910-1920, with the Model T making a big impact in the horse-drawn world. Strong will be largely snowed under during the same era, when they were still using huge rollers to pack the snow on roads for sleighs and sleds, before they started plowing them for auto travel. Farmington will be 1920-1930, after the Model A has come into mass production, and before the quick downward spiral of rail transport in the county to 1935.

Well I wanted to have as much of my cake as I could and eat it too, so I cleverly devised a plan. Different areas of the layout represent different decades and different seasons. That way I can use horses, Model T's and Model A's as well as model specific industries and whatnot that appeared and disappeared in Franklin County at the bat of an eye. The history of this railroad is such that rarely a year passes when new spurs and sidings appeared and disappeared, mills were opened or closed or literally picked up and moved to new locations. New locomotives came, old went, and some old were rebuilt into new configurations. Towns were born, grew, and disappeared. Researching all of this quickly makes you realize that you simply can't nail down what the railroad and the county looked like at any given point in any given year. Which makes it easier to justify decisions you make in what you're modeling.

Modeling all four seasons allows me to try my hand at portraying summer, fall, winter and spring, and while I'm at it, I decided I'd see how convincing a job I could do of transitioning from season to season as you move along the layout, not simply bluntly going from one season to the next.

My personal favorite aspect of the railroad was the era when Rangeley was a famous and busy resort town, full of hotels and camping lodges, steamboats and hunting guides, golf courses, sawmills, movie houses playing the latest Charlie Chaplin films and all of it serviced by the blood stream of the two-footer. To make Rangeley really come alive, it needed to be modeled in the summer, so I decided that the layout would be anchored at Rangeley in the summer, then transition to Phillips in the fall, then transition to Strong in the winter, and end at the other end of the line in the spring.

I wanted Rangeley's decade to be 1900-1910, during the heyday of the resorts, with stage coaches still operating, horse drawn wagons and very early autos owned by the rich being the norm. Phillips is 1910-1920, with the Model T making a big impact in the horse-drawn world. Strong will be largely snowed under during the same era, when they were still using huge rollers to pack the snow on roads for sleighs and sleds, before they started plowing them for auto travel. Farmington will be 1920-1930, after the Model A has come into mass production, and before the quick downward spiral of rail transport in the county to 1935.

How Dirty?

Ok, I love looking at heavily weathered dilapidated models of buildings just as much as the next guy, but does the real world really look like that? Look around you outside, and it's definitely the exception, not the norm. I'm modeling Franklin County in an era when business was booming and everything was growing. People took care of their property and pride in it. There simply weren't a lot of old buildings around. So I go for light weathering and rarely add dirt to my weathering. Rust is lightly added to machinery, and any heavy rust rust is usually found on corrugated roofing. Most of my weathering - I think of it as my 'standard treatment' - is simply applying a gray or black wash for shadowing, and hilighting by dry brushing lightly with Ceramcoat Oyster white. It's just to bring out the details of the models and people, not to make Franklin County look like it's been beaten down by a decade long dust storm.

I weather virtually everything this way. Sometimes even vegetation. I even weather riverbeds like this before pouring the resin. People, animals, everything gets the same treatment. If I add dust or dirt to anything, it's usually vehicles and wagons that have been kicking up dust on the dirt roads, as pavement was a rarity there in the time I'm modeling.

I weather virtually everything this way. Sometimes even vegetation. I even weather riverbeds like this before pouring the resin. People, animals, everything gets the same treatment. If I add dust or dirt to anything, it's usually vehicles and wagons that have been kicking up dust on the dirt roads, as pavement was a rarity there in the time I'm modeling.